At 1 a.m. on March 10, 1879, the arena at Gilmore's Garden in New York City (later renamed Madison Square Garden) was absolutely packed with screaming fans of America's latest sports craze: pedestrianism. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

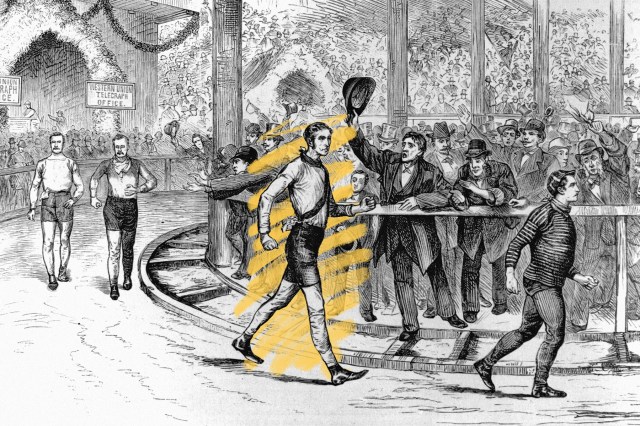

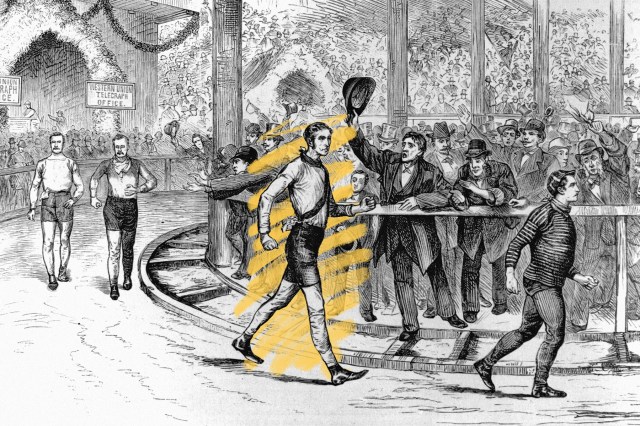

| A t 1 a.m. on March 10, 1879, the arena at Gilmore's Garden in New York City (later renamed Madison Square Garden) was absolutely packed with screaming fans of America's latest sports craze: pedestrianism. That's right, competitive walking. At the venue, fans outside tried to shove themselves in, breaking windows and scaling the roof. It was no less chaotic inside, where ticketholders scrambled on top of tables, chairs, and each other's shoulders to get a better view. That day marked the start of the Astley Belt, essentially the Super Bowl of walking. Contestants had to circle the 1/8-mile track for six days straight and reach a distance of at least 450 miles, and whoever traveled farthest was declared the winner. Athletes were not permitted to leave the track, and instead had tents or cottages where they were allowed to get a little rest or medical attention. |

|

|

| Americans' fascination with pedestrianism can be traced back to one man, a New York Herald employee named Edward Payson Weston who had a penchant for long-distance walking. Recognizing his gift for endurance, he made a bet with a friend on the 1860 presidential race, in which the loser had to walk all the way from Boston to Washington, D.C., for the inauguration. Because Weston bet against Abraham Lincoln, he found himself on a 10-day trek through ice and snow that made him a media darling. He started organizing endurance walks against other people, which grew into pedestrianism. |

|

| The sport reached the peak of its popularity in the 1870s and 1880s, at which time it was far more than a novelty. Pedestrianism spawned America's first celebrity athletes, complete with trading cards and brand endorsement deals. Weston was the first; he was so famous that scientists published studies on his urine. Many later superstars were immigrants and people of color: One of the last great pedestrian celebrities was Frank Hart, a Haitian immigrant with a record-breaking career that included a 565-mile, six-day walk. Plenty of women participated in the sport, too — as the March 1879 Astley Cup marched on in midtown Manhattan, five women were competing in their own six-day walk up in Harlem. |

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Walking distance (in miles) from the Massachusetts State House to the U.S. Capitol building | | | 473 |

| | | Admission fee for the September 1879 Astley Belt | | | $1 |

| | | Admission fee for the September 1879 Astley Belt | | | $1 |

|

|

|

| Years The New York Herald was published | | | 89 |

| | | Length (in miles) of a storied hike between the southernmost and northernmost points of the Americas | | | 14,481 |

| | | Length (in miles) of a storied hike between the southernmost and northernmost points of the Americas | | | 14,481 |

|

|

|

|

|

| | Did you know? |

|

|

There have been four Madison Square Gardens. |

|

| The arena that hosted pedestrian tournaments is not the Madison Square Garden we know today. In fact, there have been four different buildings in New York City to hold that name. The first was a railroad station converted into an entertainment venue by showman P.T. Barnum; it was later purchased by composer Patrick Gilmore and named Gilmore's Garden before being bought by William Vanderbilt in 1879 and renamed Madison Square Garden. Eventually, the original structure was torn down and a much larger venue was built in its place, with multiple stages, executive meeting rooms, and a giant amphitheater. But it struggled to stay profitable, and eventually was demolished. The third Madison Square Garden was built in 1925 a couple of miles uptown on Eighth Avenue. Then, when New York's original Penn Station was torn down in 1963, Madison Square Garden's ownership group seized the opportunity to build a new venue in its place — the current Madison Square Garden — and the previous MSG was demolished. |

|

0 comments:

Post a Comment