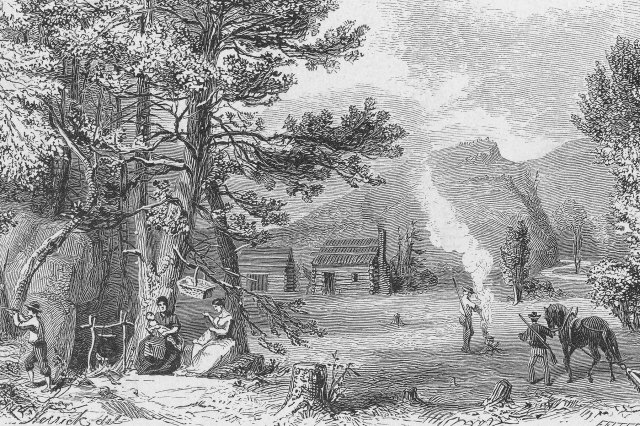

As the United States expanded westward in the 19th century, the American Southwest began to take shape, but the desert environment was unfamiliar to the colonists (many of whom hailed from Europe) and inhospitable to their pack animals. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| A s the United States expanded westward in the 19th century, the American Southwest began to take shape, but the desert environment was unfamiliar to the colonists (many of whom hailed from Europe) and inhospitable to their pack animals. In 1836, a U.S. Army lieutenant made a novel suggestion: to import herds of camels, who were accustomed to rough terrain and could go without water for a week or more. The idea was initially dismissed, but was revisited when the Mexican-American War ended in 1848 and Mexico ceded 55% of its land to the United States, including desert regions in what's now California, New Mexico, Nevada, and Arizona. Congress approved funding to bring over a herd of camels in 1855, and a Navy vessel that had been outfitted specifically for camel care sailed to the Mediterranean and spent the next five months acquiring 33 of the beasts. The ship unloaded 34 camels in Indianola, Texas — one adult camel had died, but two out of six calves born on the voyage survived. The group was known unofficially as the Camel Corps. |

|

|

| The camels proved the most useful on survey missions, helping to explore the region's harsh climates and scout locations for roads. They even proved to be great swimmers, crossing the Colorado River more successfully than the horses and mules traveling with them. On one mission, camels even led survivors to safety after the traveling party got lost in the Mojave Desert. The experiment, while considered successful by those who actually worked with the camels, was largely abandoned during the Civil War. Over the years, many animals were turned loose, and it was not unusual to see rogue camels wandering American deserts for a time: One of the most notorious camels of the era, the Red Ghost, roamed the Arizona countryside until 1893. |

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Most recorded humps on a camel | | | 4 |

| | | Global population of the wild camel species | | | 1,050 |

| | | Global population of the wild camel species | | | 1,050 |

|

|

|

| Year Arizona and New Mexico were admitted to the U.S. | | | 1912 |

| | | Median life expectancy (in years) of a camel | | | 17.8 |

| | | Median life expectancy (in years) of a camel | | | 17.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

| | Did you know? |

|

|

The Camels Corps was championed by Jefferson Davis. |

|

| When the idea for the Camel Corps was first floated by the Army, it had a champion in the Senate who helped secure funding when he became secretary of war: Jefferson Davis, who later became president of the Confederacy. He envisioned camels not as an invaluable part of surveying teams, but rather as a tool to drive Indigenous peoples off the land to make room for Southern settlers. This intention wasn't lost on the American public, and Davis regularly denied accusations that the Camel Corps was a pro-slavery plot. Southern plantation owners started using camels in their fields, and some historians suggest the camel trade was used as a ruse to transport enslaved people across the Atlantic. |

|

Lainnya dari

0 comments:

Post a Comment