On September 12, 1866, a packed house at Niblo's Garden theater at the junction of Broadway and Prince Street in New York City witnessed a unique spectacle with the six-plus-hour debut of The Black Crook. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

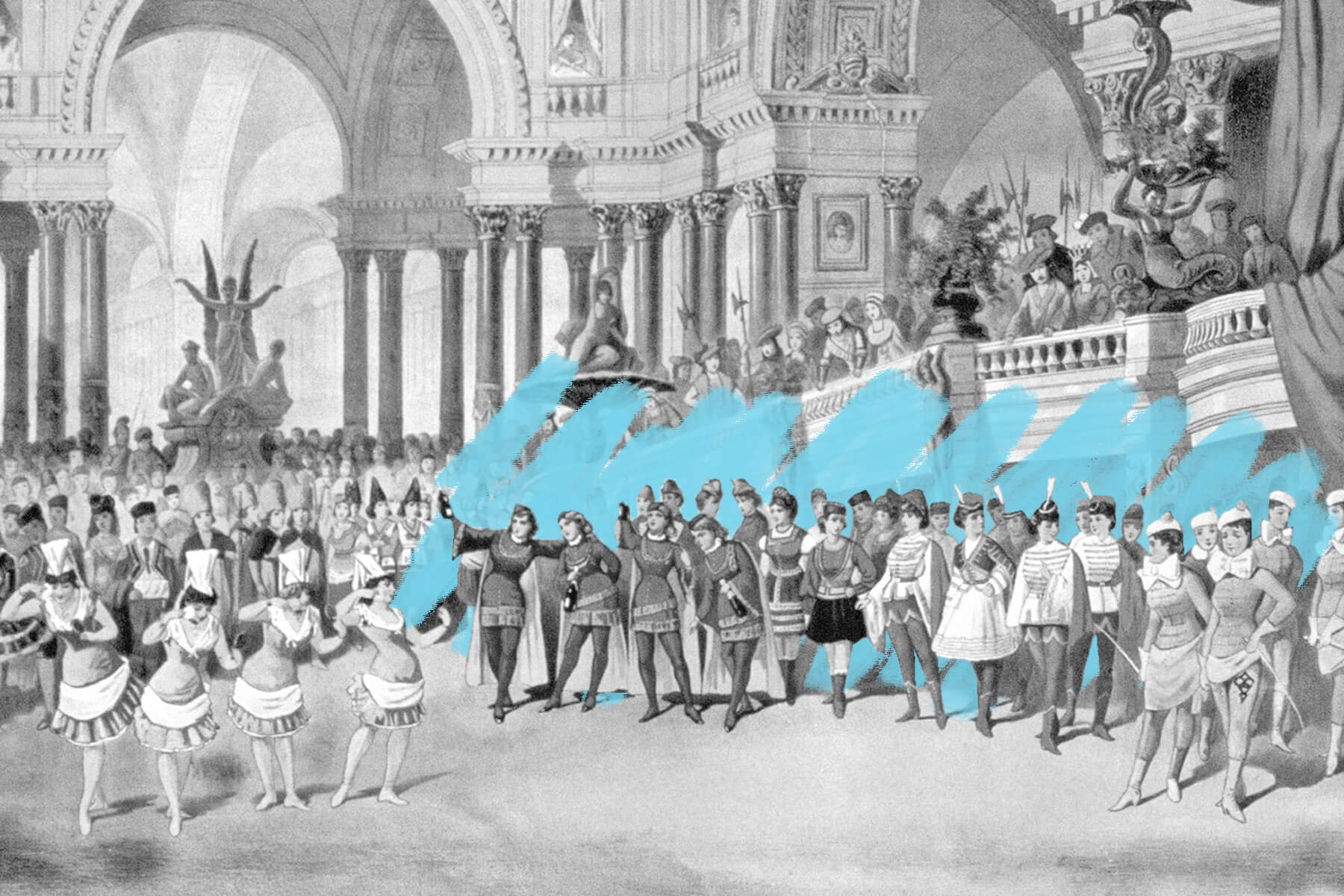

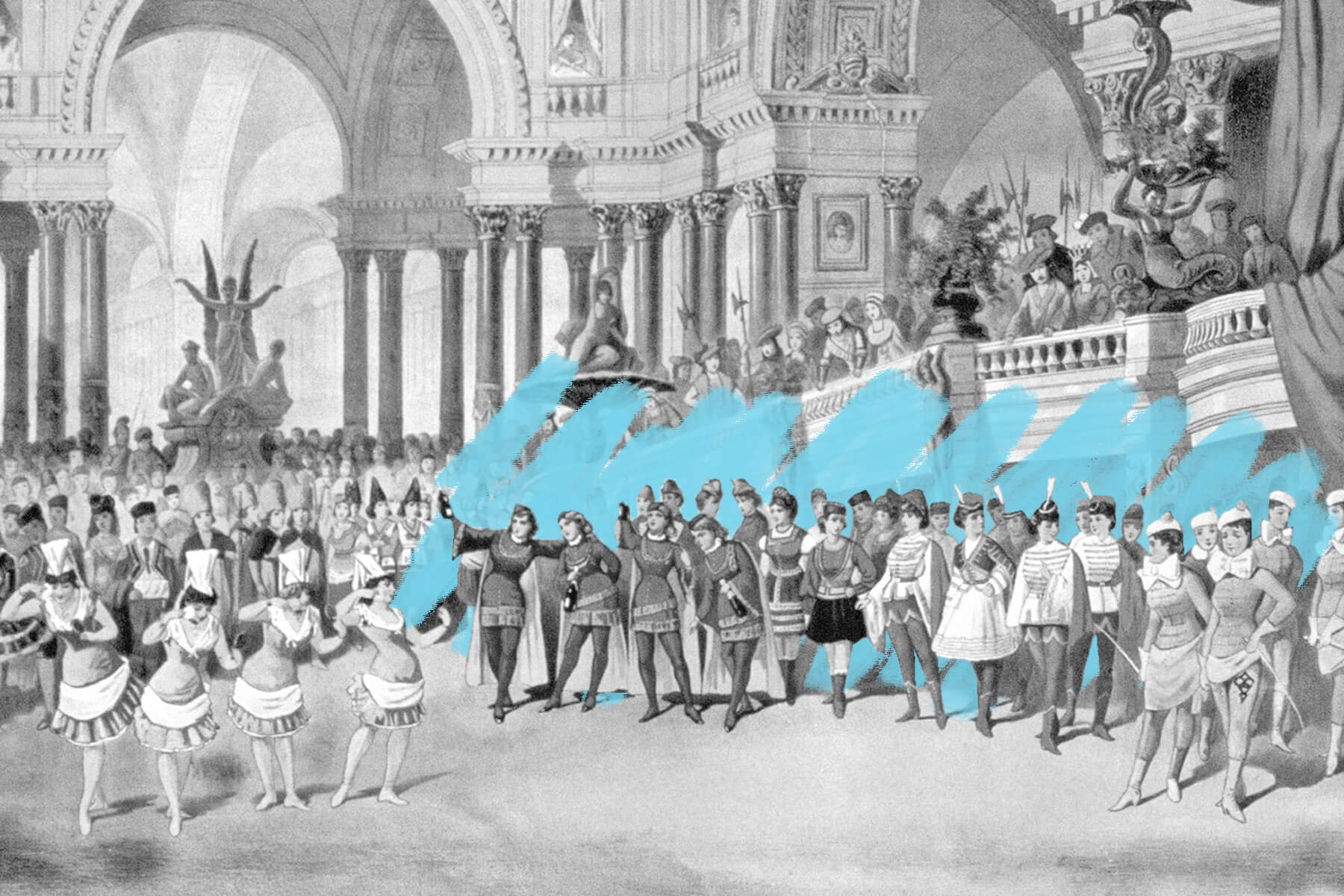

| O n September 12, 1866, a packed house at Niblo's Garden theater at the junction of Broadway and Prince Street in New York City witnessed a unique spectacle with the six-plus-hour debut of The Black Crook. Dozens of dancers in flesh-colored tights twirled around the stage as glittering fairies; ominous lighting and noises announced the onset of a hurricane; and the banter between the main characters was interrupted by such plucky songs as "You Naughty, Naughty Men." Although this was hardly the first stage performance to incorporate singing into the drama, the explosive combination of music, dancing, and elaborate set theatrics led The Black Crook to be widely recognized as the starting point for the Broadway musical. |

|

|

| The creation of the play was something of an accident. A Parisian ballet troupe had been booked for performances at Manhattan's Academy of Music, but was left without a venue when the opera house was destroyed in a May 1866 fire. Its producers subsequently struck a deal with Niblo's Garden manager William Wheatley, who determined that the troupe's attractive performers and expensive set machinery would liven up Charles M. Barras' original script for The Black Crook, a Faustian drama about a poor artist's entanglements with an evil count and an agent of the devil. |

|

| While the visual effects helped divert attention from the shaky plot, it was the scantily clad dancers who took up most of the ink in reviews and ignited the largest furor among moralists who condemned the indecent display of flesh. But the indignation only served to heighten interest: The Black Crook continued for nearly 500 performances in its first run, grossed more than $1 million, and spawned a sequel called The White Fawn, all of which demonstrated to the industry that this musical extravaganza was very much a model worth imitating. |

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Year The Black Crook takes place | | | 1600 |

| | | Operational Broadway theaters in New York | | | 41 |

| | | Operational Broadway theaters in New York | | | 41 |

|

|

|

| Broadway performances of The Phantom of the Opera, a record | | | 13,981 |

| | | Minimum seating capacity for most official Broadway theaters | | | 500 |

| | | Minimum seating capacity for most official Broadway theaters | | | 500 |

|

|

|

|

|

| | Did you know? |

|

|

"Moose Murders" is considered the nadir of Broadway flops. |

|

| If The Black Crook was the happy result of an accident, then the notorious Moose Murders represents the train wreck that can ensue when a production fails to gel into something resembling coherency. Penned by young playwright Arthur Bicknell, the 1983 play was intended to be a farcical murder mystery about a vacationing family and the strange inhabitants they encounter at an Adirondack lodge. However, things headed south when the script wound up in the possession of a first-time director, whose wife was both bankrolling and appearing in the show. The aging big-name star, Eve Arden, left after one preview due to an inability to remember her lines. While her replacement, Holland Taylor, quickly got up to speed, her professionalism couldn't offset the confusion created by such characters as a Native American caretaker with an Irish accent and a man-eating moose. At the conclusion of what turned out to be the only official performance on February 22, 1983, critic Brendan Gill summed up the disaster by noting it "would insult the intelligence of an audience consisting entirely of amoebas." Still, there was something to be salvaged from a production that became shorthand for a spectacular failure: Moose Murders occasionally enjoys a revival from a director and cast that leans into the weirdness, while Bicknell turned his painful experience into a memoir titled Moose Murdered, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love My Broadway Bomb. |

|

Lainnya dari

0 comments:

Post a Comment